Measles cases in the United States are the highest they’ve been since the country eliminated the disease in 2000. The U.S. has reported 1,277 cases since the start of the year, according to NBC News’ tally of state health department data.

Earlier this year, the U.S. also recorded its first measles deaths in a decade: two children in Texas and an adult in New Mexico. All were unvaccinated.

For the past 25 years, measles has been considered eliminated in the U.S. because it has not continuously spread over a year-long period.

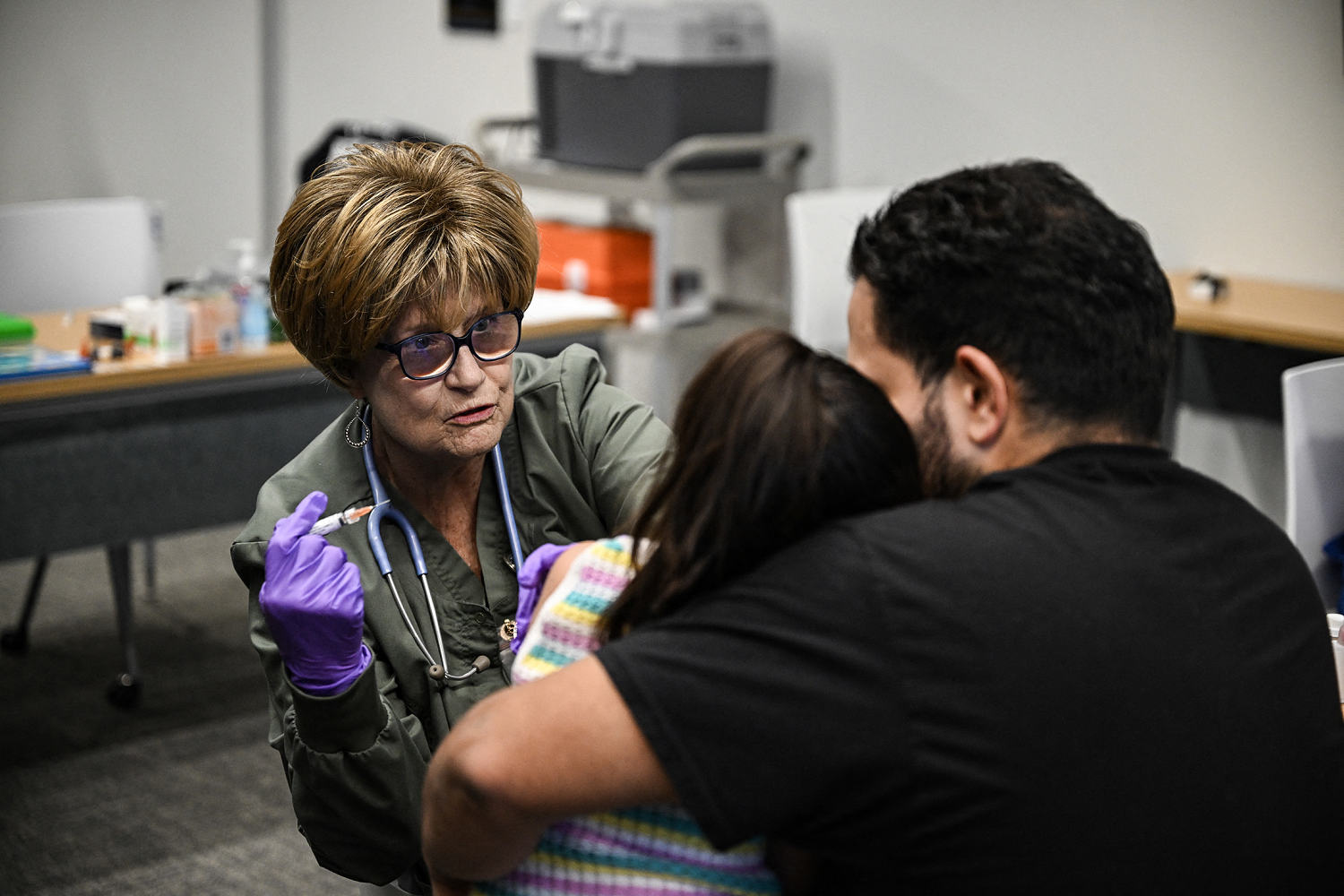

There are still periodic outbreaks, however, including one that took off in in a Mennonite community in West Texas earlier this year. Vaccination rates in Gaines County, the center of the outbreak, are particularly low: As of the 2023-24 school year, 82% of kindergarteners in the county had received two doses of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (MMR) vaccine, far below the 95% rate needed to curb spread.

Dr. David Sugerman, a senior scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said at a meeting of the CDC’s vaccine advisory committee in April that measles would have to keep spreading through January 20 of next year for the U.S. to lose its elimination status.

Most of the cases so far this year are linked to the Southwest outbreak — there have been more than 700 cases in Texas alone — though a number of smaller outbreaks, resulting from international travel, have been detected across the U.S.

The resurgence of measles can be attributed, in part, to declining vaccination rates both globally and nationally. During the 2023-24 school year, less than 93% of kindergartners in the U.S. received the recommended two doses of the MMR vaccine, down from 95% during the 2019-20 school year.

The West Texas outbreak parallels one in 2019 among Orthodox Jewish communities in New York with low vaccination rates. The U.S. recorded 1,274 cases that year. A vaccination campaign, which included a vaccine mandate in New York City and officials administering 60,000 doses in affected communities, helped contain the spread.

New York’s response was “an incredible feat and something we’re obviously trying to emulate,” Sugerman said. But he noted that the loss of Covid grant money has created “funding limitations” in Texas. The CDC slashed $11.4 billion in Covid funding last month, some of which helped state health departments respond to disease outbreaks. Each measles case may cost $30,000 to $50,000 to address, which “adds up quite quickly,” Sugerman said.

Many disease experts have also expressed concern that the federal messaging around vaccines could make the outbreak harder to contain. While Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has called for people to get the measles vaccine, he has also framed vaccination as a personal choice, emphasized unproven treatments like steroids or antibiotics and falsely claimed that immunity from measles vaccines wanes quickly.

Dr. Ana Montanez, a pediatrician who treats patients in Lubbock and Gaines County, said at a press conference in April that misinformation was the “biggest nemesis” for healthcare providers. She was aware of some patients taking vitamin A instead of getting vaccinated, she said. Kennedy has played up the role of vitamin A in helping measles patients, though it’s unclear how beneficial it is. The CDC says vitamin A can be administered under the supervision of a healthcare provider, but it’s not a treatment for the disease.

“Countering the misinformation put out there about using vitamin A for treatment of measles has been a struggle, an upward struggle,” Montanez said.

By contrast, two doses of the MMR vaccine are 97% effective against measles and offer lifelong protection. The virus is particularly dangerous for babies and young children, whose immune systems aren’t always developed enough to fight an infection. In Texas, officials recommended an early dose for babies ages 6 to 11 months. Unvaccinated children over 12 months old should get one dose, according to the state, then a second dose 28 days later.

Measles often starts with a high fever, cough, runny nose and pink or watery eyes. From there, people may develop white spots on the insides of the cheeks near the molars and a blotchy rash of flat, red spots. Severe cases can progress to pneumonia or swelling of the brain.

Roughly 1 to 3 out of every 1,000 children with measles die from respiratory and neurological complications, according to the CDC.